The illusion of alignment

Misalignment in digital projects often hides behind surface-level agreement. Cultural norms like politeness, power imbalance, and rushed decision-making lead to fragile consensus. Real alignment takes trust, open challenge, and shared definitions before delivery, not after.

This article is part one of Rethinking Digital Decisions, a series inspired by my Beyond the Promise research into digital failure.

This series will explore some of the hidden dynamics that influence digital effectiveness in cultural organisations.

Each piece looks at different aspects of how these decisions are shaped by culture, maturity, and organisational readiness, and what it really takes to make digital stuff work well.

How often have you been involved in a project where everything looked harmonious, aligned and agreed on the surface but that you knew (or felt) was proceeding with silent or undiscovered disagreement and no shared definition of success.

It feels like it happens with alarming regularity.

The real problem

Surface-level agreement (e.g. "yes, we absolutely need a new website / CRM / ticketing system / DAMS / interactive exhibit / whatever") often masks a mess of competing definitions of success, different internal priorities and unspoken hopes or fears.

What ends up looking like scope creep, overreaction to change, or poor execution is often a misdiagnosis, and is instead the inevitable result of a project simultaneously heading in multiple directions without realising it (or realising but not acknowledging it).

As I heard in the work for Beyond the Promise - "misalignment" as a cultural issue was far more of a challenge than technical concerns.

By 'alignment', I mean a genuine, shared understanding of the problem, priorities, and what success will look like, not just agreement on a deliverable. Misalignment is the absence of some, or all, of that.

Why this happens: culture, leadership, and politeness

I think that there are a few norms that exist in many (most?) cultural organisations I've worked with, in, and for that are responsible for this silent, illusory misalignment.

These include things like:

- Organisational politeness

- Power imbalances

- Vagueness about roles and responsibilities (and a related lack of ownership and accountability)

- Pressure to "get on with it" over thoughtful, reflective planning

- People making implicit (unspoken) assumptions

- Suppliers being brought in 'to solve it', before a shared understanding exists about what 'it' actually is, or what 'solved' would even look like

One particularly tricky dynamic I’ve seen is when senior leaders are expected to back a solution before they’ve had time to properly understand the problem. Often this is driven by urgency (external funding pressures, internal timelines), or the need to signal decisive leadership.

But once a solution is chosen (especially if it has then been shared with a board, funder, or the public) reopening the conversation can feel reputationally risky. Leaders can become unintentionally locked in because their intellectual credibility feels tied to the decision. Changing course might feel like admitting they didn’t fully grasp the situation at the outset.

The result is a kind of retroactive alignment where the organisation must now agree with a decision already made, regardless of whether it still makes sense. Instead of iterating or pausing to reflect, people double down. Misalignment is papered over and locked in rather than being addressed.

This is not a personal failing. It’s a structural risk in how we frame leadership, progress, and accountability especially in digital projects, where ambiguity is high and assumptions shift quickly.

And this is exacerbated by the fact that digital responsibility is often held either by a junior staff member without the influence to shape direction, or by a senior leader who may lack the time, expertise, or confidence to engage meaningfully. Both scenarios increase the risk of divergence.

Proactively avoiding misalignment means making space for rigour and direct conversations, even when that feels uncomfortable.

Time spent up front to define the problem, agree what success looks like, clarify what the solution will and won’t do, and identify who needs to be involved is not a luxury, it’s essential.

Sometimes, that means trusting a more junior (but more expert) colleague. At other times, it means leaders carving out the time to engage thoughtfully rather than defaulting to a rushed, ‘obvious’ answer.

And it requires cultures where robust, respectful disagreement is possible. Not every alignment conversation will be smooth, but without it, assumptions linger unchallenged: "well of course we would focus on x, y, or z - we 'all know' that's the priority". Except that we don't 'all know that' because the conversation has never actually been had, or it was had 5 years ago when half the people in the conversation didn't work here.

The corrosive impact of politeness

One of the most persistent barriers to alignment is what I’d call 'institutional politeness', a culture where people are so committed to harmony (or so wary of conflict) that they avoid difficult conversations altogether.

This doesn’t always come from a place of fear, it often stems from good intentions - trying to be nice, supportive, collaborative. But it can lead to silence where challenge is needed, and result in vague consensus when real decisions need to be made.

This dynamic is described in Patrick Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions of a Team, which identifies 'fear of conflict' and 'absence of trust' as foundational barriers to team effectiveness. When teams prioritise harmony over healthy disagreement, they build what Lencioni calls 'artificial harmony' - that is, an illusion of alignment that collapses under pressure. Without trust and open (healthy) conflict, teams avoid accountability, and poor outcomes are quietly tolerated rather than challenged.

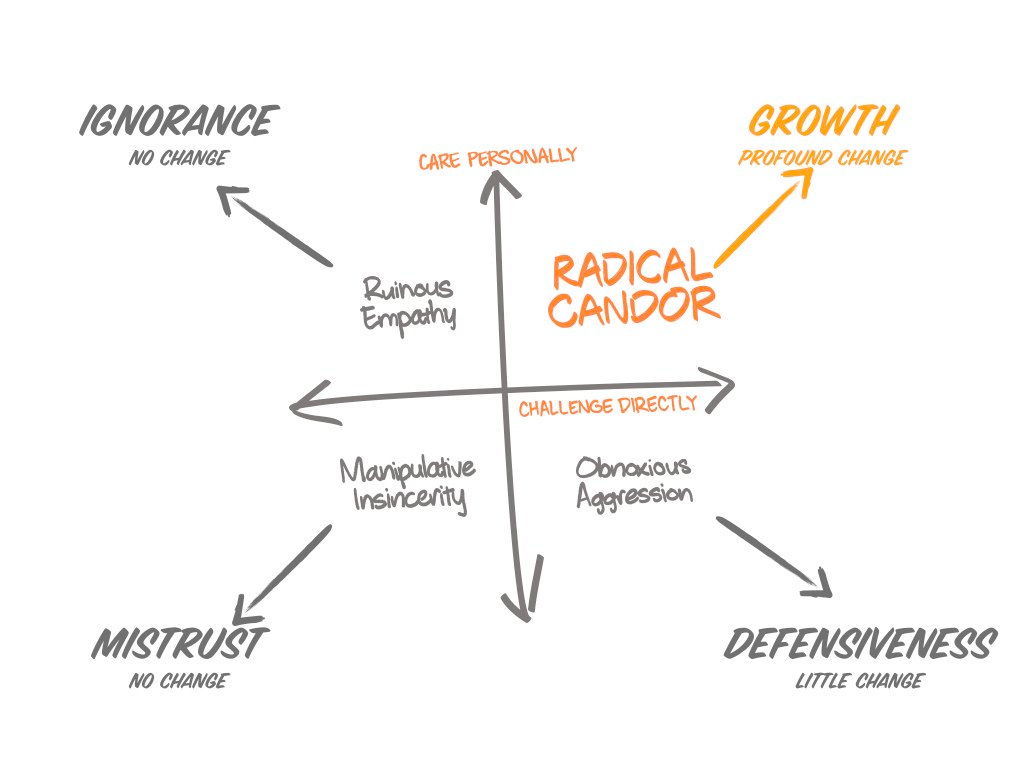

Kim Scott, in her book Radical Candor, draws a useful distinction here. The ideal, she argues, is to challenge directly while caring personally. But many cultural organisations (especially, in my experience, in the UK and US) tend to operate in a quadrant she calls "Ruinous Empathy" i.e. being so concerned with not upsetting anyone that we allow poor decisions (or no decisions) to persist unchallenged. We avoid friction in the moment, but in doing so we unintentionally store up problems that will cause greater damage down the line.

This is not just a personal behaviour issue, it’s a cultural norm. In the UK and the US (as I say, in my experience), indirectness is often the default. Feedback is softened or implied, disagreement is cloaked in polite, indirect suggestion. We expect others to "read between the lines" and if they don’t, we silently blame them.

It is interesting and illuminating to speak with people who don't come from this Anglo-centric cultural background to get a sense of just how baffling this can be when you're not used to it.

In contrast to my experience of working cultures like the Netherlands or Germany where there is a higher value placed on clarity and directness. You know where you stand, and so does everyone else (this can be quite a jarring experience at first!). Disagreement isn’t a threat to unity, it’s part of the process and an indication that the decision was reached through clear, open discussion that didn’t shy away from differences.

In an article on the value of clarity, Paul Brown (when describing potential solutions) says, "draw a line and stand behind it. Yes, someone will be annoyed. That’s the point."

An approach which could be useful in this context is 'disagree and commit' (popularised by Amazon), although this approach relies on a degree of psychological safety to be useful (and not just performative, or threatening).

Another related approach is what Dr Carrie Goucher calls 'agreement levels' (you can listen to Carrie describing how this works in our podcast chat) - this approach allows you to add nuance to your discussions, rather than simply asking the binary question of if people agree or disagree:

"For example, 'one' could be total veto. I disagree and I won't support it. 'Two' could be I don't agree, but I will back it. 'Three' could be I think we need more information. 'Four' could be I agree, but with these caveats. And 'five' could be I wholeheartedly agree. It allows people to take a position and make that clear very quickly"

Since moving to Sweden, I’ve noticed another cultural norm. Swedish workplace culture places a high value on consensus-building and inclusivity in decision-making. While this can be slow and sometimes frustrating for those used to quicker, top-down calls (👋🏽), it has a major advantage in that people are expected (and encouraged) to share their views.

Disagreement isn’t buried; it’s surfaced and worked through. The emphasis is not just on being heard, but on ensuring that everyone genuinely has the opportunity to speak. That may delay decisions, but it creates alignment that is real, not assumed or implied.

Institutional politeness, by contrast, prevents challenge, avoids clarity, and undermines trust. You don’t get genuine agreement you get performative, artificial harmony that probably actually hides a whole load of resentment. And that makes digital work brittle. If people can’t speak openly about risks, hopes, doubts, and blind spots, you end up with only partial truths. Misalignment festers, and a feeling of momentum becomes a stand-in for actual progress.

Ultimately, creating space for respectful, open disagreement is not a luxury it’s a prerequisite for good work to happen. It’s not just a question of personality, it’s a leadership issue and a structural one. Leaders have to demonstrate candour, reward clarity, and make it safe to say the awkward thing early, before it turns into something more costly later.

What misalignment looks like in practice

You rarely see misalignment at the start, it only shows up later when symptoms appear, like these:

- Scope creep that isn’t really creep, it’s delayed discovery (and acknowledgment) of disagreement

- Endless mid-project debates start about what matters most

- Stakeholder support that evaporates at the first sign of friction

- Projects that hit delivery deadlines but don't actually meet user needs or make an impact

By the point these symptoms show themselves, addressing them isn't just adjusting course it's unpicking fundamental misunderstandings that should have been surfaced from the start of the project.

What can help

Some simple practices can make a real difference:

- Pre-mortems: imagining failure in advance to surface risks and misalignment

- Shared definitions of success: not just 'launch the new site', but more like 'make it easier [with a definition of what 'easier' actually means] for users to find events and book', with agreement (or at least visibility and acknowledgment!) across roles. Even better when it includes what success won’t be (e.g. 'this phase won’t solve X yet').

- Reflective planning tools: tools that create space for thinking, not just tasking. For example:

- Digital maturity frameworks: helps teams to understand where they are, where the gaps are, and where they might need alignment

- Working assumptions logs: sometimes included on documents called RAID logs (Risks, Assumptions, Issues, Dependencies), listing key assumptions so they can be aired and tested, not ignored

- Alignment rituals: structured conversations and moments that make sure people are genuinely on the same page. For example:

- Kickoff meetings that start with purpose and priorities, not just tasks and timelines

- Project charters or one-page briefs that are reviewed and re-confirmed at key stages

- Regular 'pulse checks' or facilitated sign-offs where different teams reflect on progress and flag drift before it gets baked in

There are a few other suggestions on ways to achieve team alignment in this Mural article.

These suggestions aren’t "more process". Think of them as preventative care i.e. small investments that avoid much larger problems down the line.

Making digital work is a cultural act

Misalignment isn’t tactical, it’s cultural, and it’s preventable.

I recommend that you start by asking questions like:

- Where in this project are we assuming alignment without confirming it?

- Have we actually defined success or just described the deliverable?

- Who hasn’t been part of shaping this brief, but will be blamed if it fails?

- Are we prioritising progress over clarity? Why?

- What’s the hardest question we’re avoiding and what would happen if we addressed it?

3 key considerations

But if you do nothing else, based on working with dozens of cultural organisations navigating complex digital change of all sorts of shapes and sizes, there are three things I always recommend when improving alignment:

- A visible, shared definition of success (not just a budget and timeline).

- A culture of early challenge, not late disappointment.

- A named individual (or team) who not only owns the alignment conversation but has the authority and support to act on it.

How I can help

If this sounded familiar, and you're facing a digital project that feels slightly out of sync (or you're keen to avoid that happening in the first place) I can help.

I work with cultural organisations as a critical friend, advisor, and facilitator to:

- Untangle misalignment and surface unspoken assumptions before they become blockers

- Support reflective planning, from early-stage scoping to shared success criteria

- Design and run alignment rituals, including premortems, discovery workshops and interviews, and stakeholder briefings

- Build digital maturity, helping teams clarify roles, readiness, and strategic fit

Whether you’re kicking off a new project, rethinking an old one, or just need a second brain to make sense of the fog, I offer structured, supportive ways to bring clarity and alignment to your digital work.