The under-explored potential of shared infrastructure and expertise

Many cultural orgs build near-identical digital systems from scratch which are often costly, fragile, and rarely better than ‘just good enough’. What if we explored shared infrastructure for the basics, freeing up time and budget to focus on what really matters?

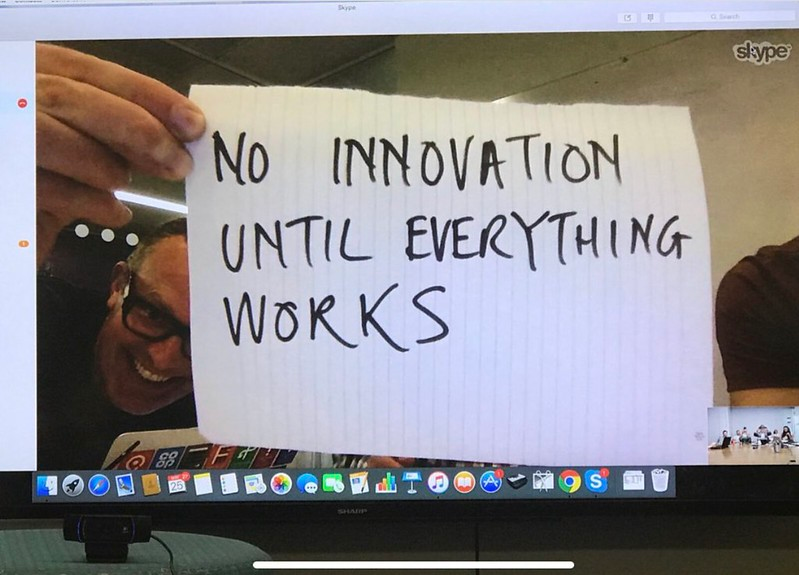

This post was partially inspired by a post from Neil Williams which re-shared this 2019 photo:

A few cultural leaders I’ve spoken with recently have raised the idea of sharing digital infrastructure or services.

This isn’t a new idea. I remember it being discussed more than 15 years ago when I was working in-house at a cultural org.

Back then, the idea made theoretical sense but the conditions weren’t quite right. It was decided that the perceived political and operational complexity outweighed any potential benefits.

But since then I think things have changed, and what’s changed isn’t just budget pressure, it’s also expectations (and, y'know, the world). Competent digital delivery is now a baseline expectation, not a nice to have. And yet, the cost and complexity of delivering even the basics (websites, digital campaigns, CRM) to a 'good enough' level remains relatively high for cultural organisations.

What’s striking in this context is how often I see organisations spending money they don’t really have to build digital infrastructure that is, fundamentally, about 80% the same as their peers. Sure there's a different visual identity, and slightly different content, but technically and structurally they are often near-identical (across a diverse array of use cases).

In a commercial environment, everyone taking their own approach might be framed as a competitive necessity. But in the publicly-funded cultural sector, where many organisations are trying to solve the same problems with limited means and are not, really, 'in competition' with one another, the duplication feels inefficient and given the increasingly tight funding environment everywhere you look, perhaps even self-defeating.

Despite some promising new SaaS tools and a handful of collaborative pilots, many organisations still default to building their digital infrastructure and experiences more-or-less from scratch when they need something. The result is a landscape full of ‘almost good enough’ systems that are resource-heavy to maintain, and rarely improve on 'the essentials' in meaningful ways (many even fail at this).

Despite this, I don’t see much appetite (yet) for building shared experience and capacity, instead of treating every digital project as a one-off puzzle tackled individually from scratch with not enough time, money, expertise, or support.

It reminds me of that Olympics-organisation dynamic, where every host city has to learn things from scratch, even though someone just went through the same process. Bent Flyvbjerg calls this 'the Eternal Beginner Syndrome', the idea that we keep having to relearn the same lessons because we don’t carry experience forward between projects.

I think that this context is partially responsible for the phenomenon that Chris Unitt described in a recent blog post, "it dawned on me that people, for whatever reason, were just calling fairly run-of-the-mill projects 'transformations'". Because in a scenario where even the most basic digital project might feel like a 'heavy lift' (because you've never done something like this before), it seems worthy of the 'transformation' label.

The false uniqueness trap

One reason why this shared approach doesn’t happen more often might be a quiet but powerful psychological barrier, the false-uniqueness effect or the uniqueness bias (I've mentioned it elsewhere recently).

Because of this cognitive bias, leaders tend to assume their organisation is just different enough that this type of collaboration or a standardised approach won’t quite work; many of us will have heard (or said) things like "our structure is too complex", "our scale is too small", "we have a unique remit".

This mindset narrows the range of what feels possible and, over time, it risks entrenching a kind of managed decline.

"most leaders tend to view their organization as being unique. This also makes them often think they have little or nothing to learn from other, more progressive organizations.

The problem with this bias is that we tend to exaggerate how special we are. That is, we can all probably think of something that makes us and others special—no matter how "similar" we are."

Collective infrastructure isn’t just a matter of willpower or overcoming bias. Governance, funding models, and coordination are notoriously tricky, and they’re some of the reasons earlier attempts never stuck.

Of course every organisation is different in some way, and there are some situations when a custom, tailored approach is required. But that doesn’t mean we need bespoke digital solutions in every situation.

In many cases, it makes far more sense to adapt our ways of working to fit good-enough and widely-used tools rather than commissioning fragile, expensive systems that don’t quite meet our needs.

This approach would then free up some much needed capacity for us to be able to focus, and do a better job, in the areas where true difference, and individuality does actually exist and matter.

Shared tracks, different trains

When Britain built its railways, no single town or city could have made the system work alone. The power came from shared tracks, standards, and signals, which allowed countless operators to run their own services while relying on a common backbone.

Digital infrastructure in the cultural sector feels similar. Every organisation runs its own train - its own programmes, audiences, and mission. But many are still laying their own tracks for things like websites, CRMs, and ticketing systems. The result is expensive duplication and fragile networks.

A more sustainable future might look like shared tracks and signals, freeing each organisation to focus on where they’re going and who they’re carrying, rather than all building versions of track for the same route.

Not outsourcing thinking, just execution

This isn’t a call to outsource strategy or creativity. Cultural organisations should absolutely remain in charge of their digital thinking, goals and direction.

But when it comes to delivery (e.g. campaign execution, tech infrastructure, procurement) I really do think that it’s worth asking could we do this better together?

Some of the most common pain points such as campaign delivery, CRM and ticketing, common integrations, even backoffice IT support aren’t really strategic differentiators. They’re foundational enablers. And the fact that many organisations are paying just enough to get by, but never enough to thrive or really improve, is a sign that it might be time to revisit the case for shared execution models.

If nothing else, it might free up some resource to invest in the more interesting questions: how we better connect with audiences, how we build capacity, and how we design for real impact in a digital world.

It's already happening, sort of, or maybe it used to?

I am aware of more than one brief that has gone out, or project that has been launched, recently where a coalition of cultural organisations has come together to try and explore shared challenges. These mostly seemed to be focused on understanding audiences.

But I've not seen this collaborative approach being taken in (m)any other areas, maybe I'm simply unaware of what's happening? I'd love to be proven wrong on this. Art Fund's Art Tickets product was an obvious example of this approach, although that product is now closed down.

This approach could also be a way of the sector unlocking the commercial value of its expertise.

I remember, and again this was 15+ years ago, that FACT in Liverpool used to hire out their video production team to create video content for other cultural organisations. Ostensibly I think this was because they wanted to create cultural content for a video platform they'd developed, but for me (as a digital manager at a cultural org at the time) it was a cost-effective way to bring in high quality video production capacity as and when I required it and, presumably, a useful income stream for FACT.

This isn’t even a particularly new line of thought. Back in 2012, Patrick Hussey speculated in the Guardian about a shared sector-wide database: "The answer is simple enough: the time might just have come for an ambitious, shared database. Imagine every cultural organisation using one system to capture their back office, web and marketing performance, then converting that data into useful insights for other sector activities."

That vision never materialised as he described it (although the Audience Agency was heading in that direction prior to some strange decisions about funding), but it perhaps shows how long the sector has been circling around this idea without quite finding the conditions to make it stick in its most useful/impactful form.

In 2013, Dr Oonagh Murphy argued that more large cultural organisations should offer their expertise to less well-resourced peer organisations, for free.

"Rather than simply mirroring the ethics and existing models for corporate social responsibility (CSR), the cultural sector could adopt and adapt a new model tailored to the good of the cultural sector as a whole. CSR could become cultural sector responsibility – an ethical model that allows large national cultural organisations to consider the impact their work has on developing the cultural sector as a whole.

This model could inform how these organisations disseminate information to medium-size and small grassroots organisations. Ultimately, the cultural sector is stronger together. Small organisations provide the foundations for those that go on to work in the top national institutions, and if small cultural organisations are being left behind digitally, then who will train the next generation of creative technologists needed to lead the digital departments of the Royal Opera House, National Museums Scotland, or the Royal Ballet?"

How might this happen?

If we’re serious about doing digital differently and more sustainably across the cultural sector, then we need to move beyond just describing difficulties and start testing potential alternatives and solutions in low-risk, practical ways.

None of this is easy. Shared approaches raise questions about ownership, decision-making, and sustainability. But there are low-risk ways of testing what might work in practice without committing to large-scale, permanent change.

In the spirit of trying to contribute potential solutions, here are a few early steps that might help work out ways forward.

Map the overlap, not just the difference

Start by identifying where needs truly align across organisations.

This doesn’t need to be a sector-wide audit, just a small cohort of willing partners comparing notes on the systems they use, the gaps they face, and the kinds of support they wish they had.

Even a shared spreadsheet or a roundtable could be a useful place to begin. This helps shift the framing from “What makes us different?” to “Where are we actually the same?”

Set up lightweight pilots, not permanent alliances

Start small. A fixed-term experiment between 2-3 organisations to test shared IT support or pooled campaign delivery services could offer valuable insights.

Frame it as a learning opportunity and a pilot, not a merger. Success doesn’t have to mean arriving at a definite solution or approach, it could simply be a better-informed understanding of what might (or might not) work further down the line.

Learn from where it’s already happening

There are already signs of collaborative working around audience data and insight such as shared segmentation models or regional and national audience research projects.

Could we extend that mindset into delivery and infrastructure? What would it take to adapt existing partnerships or consortium models to cover a bit more of the typical tech stack of a cultural organisation?

Look outside the sector for models

Other sectors such as health, education, and local government have long-standing shared services models (LocalGov Drupal is an obvious digital example).

Some work brilliantly, others very much don’t. But they offer useful templates for things like pooled procurement, shared back-office infrastructure, or joint venture vehicles.

These could inspire experiments, or at least initial conversations, specifically focused on the particular ambitions and ethos of the cultural sector.

Focus on foundational (enabling), not strategic, layers

Execution in areas like cloud hosting, CRM administration, ticketing integrations, digitisation and digital asset management, and campaign fulfilment seem ripe for shared approaches.

These aren’t where cultural organisations win hearts or deliver missions, but they are essential for making the basics work well.

This is the activity that lives most obviously in the 'Enable' zone of my 3 Modes Model.

Start by identifying one area where collaboration could reduce cost or improve quality without touching brand, mission, or autonomy.

Co-invest in shared people, not just systems

Much of the value in digital delivery lies in the people who make it work. Instead of hiring under-resourced solo roles and expecting them to deliver on an unrealistic laundry list of responsibilities, could organisations co-fund specialists for example, a campaign manager, analytics lead, or integrations developer who supports a small group of partners on a shared basis? Shared people can often bridge needs better than shared platforms.

We have seen examples of this with the Digital Culture Network in England - they are a small team trying to service the entire cultural sector, but I think DCN proves the idea of bringing in subject matter experts to support multiple cultural organisations across the things that matter when it comes to digital can be really impactful.

Talk about it, openly and honestly

This may be the most important step of all: starting to have these conversations publicly, without judgement. Ask questions, share frustrations, describe the hidden costs of duplication. Writing a short blog post, hosting a roundtable discussion, or forming a working group could help turn quiet observations into shared challenges and a shared will to fix things.

Normalise before you customise

A final thought. Even if you're not going to share expertise or infrastructure - wayyyy too often I see organisations try to force off-the-shelf systems into overcomplicated legacy structures or worse, commissioning expensive, custom-built solutions to fit an outdated (and often inexplicable) status quo.

Next time you're considering a new digital system, maybe ask questions like: what would it take to review and then standardise or simplify our processes so we can use something tried and tested?

Sometimes uniqueness is justified. But in my experience, more often than not, a small shift in working practices would be more impactful (and far more affordable) than building a bespoke system that ends up being fragile, fiddly, and frustrating.

The opportunity in front of us

The cultural sector is full of creativity, purpose, and ambition but if we want our digital infrastructure to support that energy rather than divert and drain it, it seems we probably need to start to think differently about how we invest and deliver.

Shared services and infrastructure won’t be right for every context, but I think they deserve more serious attention.

This is one of the type of things that I hope a future digital community of practice might be able to explore.